Reflections on fear from two very different experiences

By Jacqueline GaNun

Oct. 7, 2025

Read this post on Substack here.

PARIS — The night before I went swimming with sharks, I got about three hours of sleep. This was partly because somebody in my hostel room snored, partly because feral roosters started crowing at 4 a.m., partly because my friend Alex and I had a few drinks the previous evening, but mostly because I was so nervous. I knew logically sharks don’t bother people unless by accident or mistaken identity — and because I was choosing to dive in their home, I was accepting that risk regardless — but logic oftentimes doesn’t help when your nervous system is operating on fear.

As we slunk out of our shared room at 6 a.m., trying and probably failing to not wake up our temporary roommates, I thought I might throw up. I was frantically searching for a reason to back out then just as manically re-convincing myself it was going to be great. I had already paid for the trip, I had already enlisted Alex, I likely wouldn’t lose an extremity, if I did lose an arm or leg I’d have an interesting story, et cetera.

On the boat ride out to the dive site, I reminded myself that part of the reason I wanted to do this in the first place was to face my fear. I wanted to be the kind of person who wasn’t afraid to swim with sharks, or perhaps more aptly, someone who was afraid but did it anyway.

Sharks on Hawaiʻi’s North Shore are used to crabbing boats because the seafloor slopes more gently than it does around the rest of O‘ahu. For them, a boat often means a free meal, and they were therefore immediately curious about our vessel, especially after the captain revved the engine a few times. The Galapagos sharks darting up to the boat were dark gray, very long and very fast, slicing back down into the water as quick as they came. Nearly hyperventilating, I botched my entry into the ocean, splashing gracelessly down the last two ladder steps when my flippered feet missed the narrow foothold.

I held my breath for a minute as my eyes adjusted. As the lithe gray shapes gliding below me came into focus, the strangest thing happened: my fear completely dissipated. There were more than 10 Galapagos sharks coming within feet of our group, completely uninterested in us while they cruised around in search of a meal. Tiny silver bait fish flitted around, too small for the sharks to bother with.

In awe, I breathed slowly through my black standard-issue snorkel, swimming in long, smooth strokes — “getting into shark mode,” as our guide diver instructed us — and dove down again and again, getting closer to the sharks every time, ultimately coming within about two feet of a few. The sharks were muscular and graceful, precisely engineered to slice through the water and turn on a dime. The sunlight through the water left dappled marks on their skin, making some of them look almost like tiger sharks. They were beautiful.

(Photo/Ro O’Rourke, @rowouldgo)

After climbing back into the boat, my most pressing thought after “holy shit I just swam with sharks” was “I’m so glad I didn’t bail last night, or this morning, or on the boat ride out 30 minutes ago.” Had I let my fear win, I would not have had this astounding experience. And had I let fear win three weeks ago, I would not have moved across the ocean to a city in which I knew nobody.

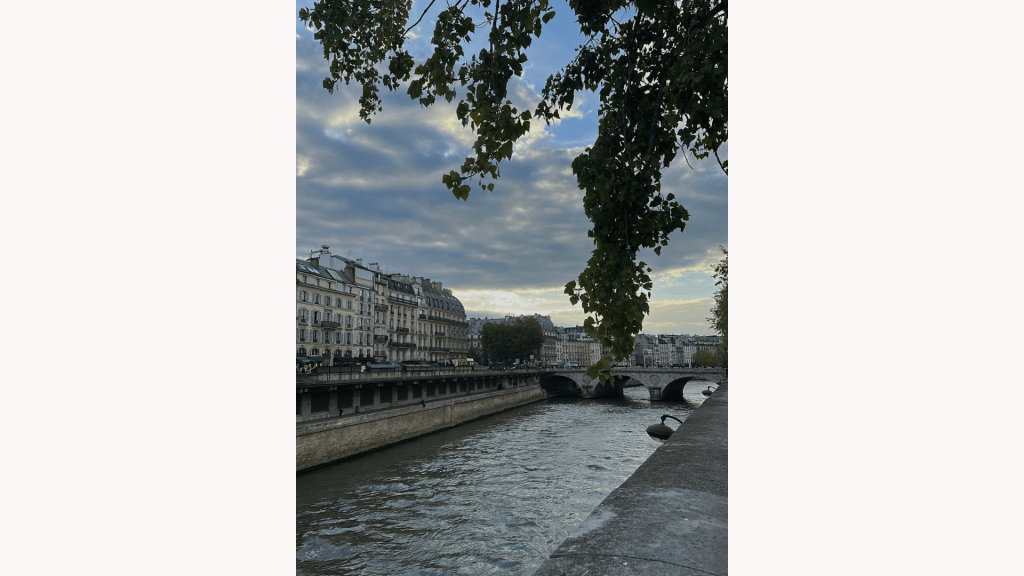

In the weeks leading up to my red-eye flight to Charles de Gaulle, I recognized the same self-sabotaging thoughts pushing me to stay firmly in my comfort zone. I’ve dreamed of living in France since at least middle school. I spent hours working on an application for an English teaching assistantship, eagerly accepted the position, and told people how excited I was to move. But when the moment was actually here, I wanted nothing more than to return to what was easy and comfortable.

Research has shown that uncertainty makes our anxiety worse, which probably makes intuitive sense to all of us. Who hasn’t gotten a pit in their stomach when applying for a job, going on a first date, or submitting a final paper? The key, though, is pushing past this immense obstacle — in the same paper, the authors write: “By avoiding situations in which negative outcomes are expected … the anxious individual cannot accumulate disconfirmatory evidence or learn about safety cues and therefore consolidates biased expectancies.” In less jargon — you must do things that scare you. No growth happens within your comfort zone.

I know this is easier said than done, and I also know I’ve been lucky to cushion my experiences. There were two safety divers on my shark swim, and I moved to France through a program with a staff to which I could reach out if I were in an emergency. But these guardrails didn’t entirely take away the anxiety I felt about either experience.

If I’m being honest, my discomfort surrounding moving to France — away from my family, friends, routines, and native language — has not disappeared yet, and maybe it never will. Being a foreigner will always be difficult in some way, even with all the privileges that come with doing it as a result of my own agency and not necessity, such as fleeing famine or war. But like in the shark dive, I believe all the rewards are on the other side of my own fear.

In “Let My People Go Surfing,” Yvon Chouinard writes that “real adventure [is] defined best as a journey from which you may not come back alive—and certainly not as the same person.” I’m choosing to think of my time in France as an adventure, and while I do wish to remain alive, I hope I don’t return as the exact same version of me I was when I left.

(Photo/Jacqueline GaNun)

Leave a comment